Chapter 4: Professionalism - What to do when things go wrong

Post date: 01/10/2015 | Time to read article: 6 minsThe information within this article was correct at the time of publishing. Last updated 18/05/2020

The overwhelming majority of patients receive safe and effective care. However, when things do go wrong, it can be catastrophic for all involved. Part of being professional is having the knowledge and awareness to deal with such situations effectively.

Good communication lies at the core of rebuilding trust and supporting healing for the patient, their loved ones and the healthcare team involved. Poor or no communication compounds the harm and distress that has already been experienced. MPS has long supported and advised members to be open with patients when something has gone wrong.

The significant cultural shift in the relationship between the medical profession and patients over recent years has changed both the definitions of professionalism, and how that professional should respond when things go wrong. The traditional, paternalistic doctor–patient relationship has been largely replaced by a doctor−patient partnership, where patients can rightly expect open and honest communication and shared involvement in decision-making: “no decision about me, without me.” Patients increasingly see themselves as consumers, and have consumer expectations. Medical professionals have to respond accordingly.

What do patients want when things go wrong?

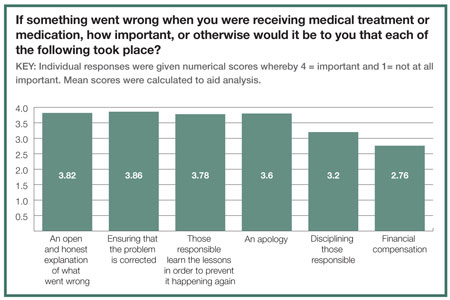

Most patients want doctors to be open and honest about the mistakes that have been made. An MPS survey on openness found that 95% of people are most likely to think that it is ‘fairly’ or ‘very important’ that they receive an open and honest explanation of what went wrong, or ensure that the problem that occurred is corrected.32 A similar proportion, 94%, think it is important that those responsible learn lessons in order to prevent it happening again, while nine in ten say that it is important that they receive an apology.

Similarly, many studies show that patients take legal action primarily because they are angry – often because they are given incomplete or delayed information about what happened and why. The majority of patients say that the main reason they initiated litigation was ‘to make sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else’. Patients want information, and they want that information used to make healthcare safer.

Duty of candour

From 1 April 2015, a duty of candour applies to all health and social care providers regulated by the CQC, including GP practices.

The duty, which was introduced by the government through regulation 20 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014, applies to NHS organisations such as trusts and foundation trusts and bodies including GP practices and care homes.

How it affects you

Under the terms of the new duty, you need to make sure that your practice acts in an

open and transparent way:

- With relevant people

- In relation to care and treatment provided

- To service users

- In performing a regulated activity.1

After becoming aware that a notifiable safety incident has occurred, you must:

- Notify the relevant person as soon as is reasonably practicable (CQC guidance refers to the ten days required by the NHS standard contract)

- Provide reasonable support, such as providing an interpreter for any discussions, or giving emotional support to the patient.

Your notification must:

- Be given in person by at least one representative of the practice involved, and then

followed by a written notification - Provide a true and accurate account of the incident

- Provide advice on what further enquiries into the incident are required

- Include an apology

- Be recorded in a written record, which should be kept securely.

What is a notifiable safety incident?

The regulation states that there are two meanings of a notifiable safety incident; one for a health service body, the other for registered persons – registered persons being GPs and primary care dental practitioners.

According to the regulation:

1. appears to have resulted in –

- the death of the service user, where the death relates directly to the incident rather than to the natural course of the service user’s illness or underlying condition

- an impairment of the sensory, motor or intellectual functions of the service user which has lasted, or is likely to last, for a continuous period of at least 28 days

- changes to the structure of the service user’s body

- the service user experiencing prolonged pain or prolonged psychological harm, or

- the shortening of the life expectancy of the service user; or

2. requires treatment by a health care professional in order to prevent -

- the death of the user, or

- any injury to the service user which, if left untreated, would lead to one or more of the outcomes mentioned in sub-paragraph (a).

What is harm?

“Harm”, as listed above, is further defined in the regulation as:

• Prolonged psychological harm - means psychological harm which a service user has experienced, or is likely to experience, for a continuous period of at least 28 days.

• Prolonged pain – means pain which a service user has experienced, or is likely to experience, for a continuous period of at least 28 days.

About the duty of candour

Introduced for NHS bodies in England from 27 November 2014, the key principle of the duty of candour is that care organisations have a general duty to act in an open and transparent way in relation to care provided to patients. The statutory duty applies to organisations, not individuals.

Further information

The Care Quality Commission, Regulation 20: Duty of candour. Issues for all providers: NHS bodies, adult social care, primary medical and dental care, and independent healthcare (March 2015) –www.cqc.org.uk/content/regulation-20-duty-candour

1 “Regulated activity” is defined by the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006

What should openness look like?

Doctors have a professional and ethical obligation to be open and honest when things go wrong. GMC guidance states: “You must be open and honest with patients if things go wrong. If a patient under your care has suffered harm or distress, you should:

(a) put matters right (if that is possible)

(b) offer an apology

(c) explain fully and promptly what has happened and the likely short-term and long-term effects.”33

When things go wrong, saying sorry is not enough – as the graph below, taken from an MPS survey, shows. Patients want an explanation of what went wrong and why, and doctors need to rebuild the relationship of trust. Notably, patients are least likely to think that financial compensation is important – 52% think it is fairly or very important.34

Case study: The importance of being open

I presented at the Emergency Department (ED) with a terrible pain down my arms and back after a fall. After some investigations, which came back negative, I was given some painkillers and sent home.

The next day, I went to see my GP because I was in so much pain. She prescribed me four different painkillers and advised me the pain should settle in a week or two.

Six and a half weeks later, the pain was as bad as ever. I was referred to a neurologist, who thought I might have a slipped disc. He arranged a CT scan, which showed that a vertebra in my neck was broken in three places.

I was horrified that the fracture had been missed for so long. I now know that I could have been paralysed and should have been placed in a neck collar immediately. Instead, I had spent the past six weeks following my doctor’s advice to be as active as possible, even going for a 10k run.

I understood that the doctors missed the fracture because they were more concerned to find out why I had had the fall. They were trying to do their best. We’re all human and fallible.

Immediately, the neurologist acknowledged they had missed the fracture and was very open about the mistake. He apologised, but at that point, saying sorry wasn’t high up on my agenda. I was more interested in what was going to happen and whether I was going to be ok.

He didn’t try to cover anything up and asked for an internal investigation straightaway. He also said that I was under his care. This made me feel like I wasn’t just another patient being moved from one place to another. This doctor would look after me. He reassured me everything would be ok.

Once I was feeling a little better, I kept running through my mind what could have been. I knew something bad had happened, and that something even more catastrophic could have happened. I realised there was a problem in the system; another woman on my ward also had a slipped disc which wasn’t picked up in the ED. I didn’t want this to happen to anyone else. I decided to write a letter of complaint.

The hospital wrote to confirm receipt of my letter and stressed they were taking the complaint seriously. However, I waited months for a response. The time lapse made me think they had something to hide, or were scared of legal action.

After months of chasing, when the response came, I was initially relieved. However, the hospital hadn’t answered my key questions. They apologised, admitted the mistake, and explained they were changing systems, but they didn’t comment on whether their failure to diagnose had made my condition worse. I wanted someone to take responsibility for what had happened to me.

By Farzana Hakim

You can either download a PDF version of the guide by clicking here or use the links at the bottom of each page to read online.

| << Professional Expectations | Fitness to Practice (FTP) procedures >> |