Doctor’s orders vs patient choice

Post date: 01/06/2013 | Time to read article: 5 minsThe information within this article was correct at the time of publishing. Last updated 18/05/2020

Doctor’s orders vs patient choice

Earn CPD points by reading this feature on shared decision making. Dr Paul Nisselle explores how to move from bedside to beside

Earn CPD points by reading this feature on shared decision making. Dr Paul Nisselle explores how to move from bedside to beside

In 1871, in an address delivered to the graduating class of the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, Oliver Wendell Holmes said: “Your patient has no more right to all the truth than he has to all the medicine in your saddle-bags... he should get only just so much as is good for him.”

This attitude, perhaps less bluntly expressed as ‘benevolent paternalism’, pervaded medical behaviour for at least the next century – a sort of “Father knows best” culture. It was based on a willing acceptance by the profession to accept the ‘burden’ of making difficult decisions for the patient, sparing them the agony of making such decisions themselves.

History of consent

Indeed as late as 1964, Lord Denning presided over a case in which a BBC broadcaster, when recommended a sub-total thyroidectomy for thyrotoxicosis, was not warned of the risk of laryngeal damage. That eventuated and the broadcaster never worked in radio again. Lord Denning, in his address to the jury said: “What should a doctor tell a patient?

The surgeon has admitted that on the evening before the operation he told the plaintiff that there was no risk to her voice when he knew that there was some slight risk; but that he did it for her own good because it was of vital importance that she should not worry... he told a lie; but he did it because in the circumstances it was justifiable... But the law does not condemn the doctor when he only does what a wise doctor so placed would do.”

"The pendulum in medical behaviour is swinging away from the medical despot model to the other extreme, the ‘servile technician’ model"

Consent today

How can that right be exercised, if the patient’s decision is not appropriately informed, or indeed if they took little part in the decision-making process? Consent, to be valid, at law, must be informed and given voluntarily (that is, not under duress) by a competent patient.

Put poetically, the pendulum in medical behaviour is swinging away from the medical despot model to the other extreme, the ‘servile technician’ model. The latter doctor thinks their duty is to provide comprehensive information on all available treatment options (and the ‘do nothing’ option), but not to seek to influence the patient’s decision by giving advice. An “all care but no responsibility” model.

Bedside v beside

The reality is that both cultures are inappropriate. We are not technicians, we are ‘professionals’ in the broadest definition of that word. We care what happens to our patients, and that means helping them make safe and appropriate healthcare decisions. That does not mean we should try to make those decisions for them.

"A newer concept drops the first ‘d’ so it becomes ‘beside manner’, underscoring that our job is to be ‘beside’ the patient, guiding them in their medical journey"

The term ‘bedside manner’ was usually applied to avuncular, medical paternalism. A newer concept drops the first ‘d’ so it becomes ‘beside manner’, underscoring that our job is to be ‘beside’ the patient, guiding them in their medical journey.

What is called informed consent is a necessary, but narrow legal construct. Shared decision making is a broader, ethical construct. We sometimes need to protect patients from themselves by advising against bad medical decisions and even sometimes by refusing to comply with a patient’s request.

It is easy to forget that:

- Patients can request treatment

- Patients can refuse treatment

- Patients cannot demand treatment.

This may sound like it is a retreat to medical paternalism, but if you form a view that what the patient is asking you to do is not in their best interests, you have a moral duty not to do it. Sometimes that’s obvious. The addict in withdrawal desperately wants you to ease their withdrawal symptoms, but providing what they want may be unethical, and not in their medium or long-term interests.

Sometimes it’s less obvious. For example, is a patient’s expectations of what a requested cosmetic procedure will do for them so unrealistic that the ethically correct thing to do is to refuse?

Find-it/fix-it

The medical process has traditionally been seen as a Find-It/Fix-It model, answering the questions:

- What’s wrong with this patient?

- What can be done for this patient? But there’s also an important third question:

- What should be done for this patient? That’s better expressed in the first person –

- What should I do for this patient?

Best interests

Remembering that ‘professionals’ put aside self-interest, the next question should be “Is what I propose transparently motivated by the best interests of the patient?”

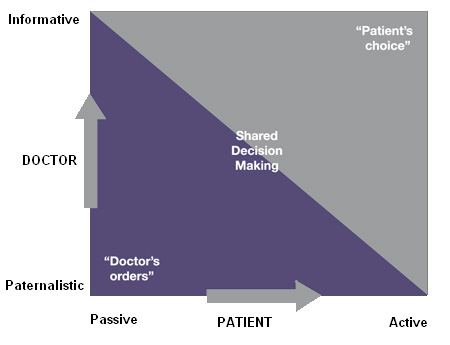

So neither doctor’s orders nor patient’s choice will do. The diagram below illustrates some of the hazards.

Patients who wish to be passive in their health affairs will want to seek out paternalistic doctors. Patients who want to be active, indeed to direct their treatment completely, will seek out informative doctors.

As a doctor who in recent years has been more commonly a receiver of medical treatment than a provider, the attitude of my treating doctors has been polarised around two extremes (and I recognise that I exaggerate):

- “You might be a doctor but to me you’re just another patient, and you’ll do as you’re told”

- “Hello, doctor, what would you like?” (with hand hovering between prescription pad and referral pad)

Happily my GP manages me with collegiate courtesy, listens to me closely and moves us towards decisions with which we are both comfortable.

Looking for evidence for your eportfolio?

MPS is committed to education and training. That is why we have developed online learning modules on the topics covered in this article, so that you can download a certificate of completion as evidence of your learning for your ePortfolio.

We have just made available on our website an e-learning module, “Doctor’s Orders or Patient’s Choice” in which Professor Stephen Rollnick, Professor of Healthcare Communication at Cardiff University, works through two difficult case scenarios to show how techniques used in motivational interviewing can help in the management of such cases.

What to do next…

- Once you’ve read this article, simply go to www.mps.org.uk/e-portfolio where you can register for the E-learning platform

- You’ll need your membership details to register and log on

- Once logged on, you will be able to access the modules highlighted on the home page

- You can complete the modules at a time that suits you

- Download your certificate of completion and any supporting notes

- Other modules on a wide range of subjects can also be accessed through the E-learning platform.

MPS workshops

MPS provides a half-day workshop, Mastering Shared Decision Making, which is part of MPS’s popular communication workshop series. For more information visit:www.medicalprotection.org/uk/education-and-events

More information

- Access the MPS library of factsheets – this includes detailed information on the law around consent and confidentiality

- Visit the handbooks and booklets section, to read more about consent and the ethical maze that is modern medicine.